|

Email your photos & stories |

|

For the Korean War site by Simon Coy

|

Cranwell

LINKS

89ers since 1966

Members Actions, Events & Stories

The following section is a mix of stories (Short & Long) of individual actions and experiences some amusing, some very sad, some life changing but all historic. All the stories demonstrate the professionalism, dedication, and flexibility united by comradeship within 89 Entry, the RAF College and the Royal Air Force in the latter part of the 20th century - "Superna Petimus"

It is in time line order.....

1. Andy Griffin - First tour 56 Squadron - 1968

2. Pete Thompson - 74 Squadron - 1968

3. Dick Shuster AFC - 81 Squadron - 1969

4. Dick Northcote - Shortless in Tengah - 1970

5. Frank Whitehouse - 74 Squadron - 1970

6. A weekend in Las Vegas - 1974

7. The Falklands War - 1982

1968 - First Tour - Lightnings in Cyprus - Andy Griffin

Andy

Griffin (89B) completed the Lightning OCU in June 1968 together with Ron Shimmons

(89B), Frank Whitehouse (89B). They were 3 of 4 pilots on the course. Andy

reports that unconventionally their instructor gathered them together and announced that there was one posting to Singapore (74 Sqn) one to Cyprus

(56 Sqn) and 2 to Wattisham. The 4 names were put in a hat. First out

was Frank to Singapore, second Andy to Cyprus and the other 2 to Wattisham. So

Andy went off to Akrotiri to join 56, his first operational squadron.

| 56 squadron was very experienced and independent having more or less written its own rules and training schedule. These were far more realistic than in the UK. Examples included combat training down to 7,000ft ( UK squadrons were restricted to 20,000ft) with a great emphasis on the daytime low-level fighter-bomber threat. Add to this the fact that the radar providing control and surveillance was at the top of Mount Olympus and could see a low level target at a range of 100nm, and they were ready for anything. The main limitation was the limited range of the Lightning F3. |  |

56 squadrons primary task was to protect the local airspace. 2 aircraft were

held on 10 minutes standby during daylight hours (and 90 minutes at night). These were used to scramble, intercept and identify any aircraft that might be seen to threaten the sovereign base areas of Cyprus.

Their main day-to-day trade came from Soviet-manned TU16 “Badger” bombers used for maritime reconnaissance

mainly watching US 6th Fleet. They operated out of Egypt and carried Egyptian markings

but with trim tabs painted red if they were soviet manned.

|

Up until June 68 the squadron we

had not achieved an interception against a Badger, because as the

Lightnings got airborne the Badgers always turned away. Clearly they were

monitoring all RAF frequencies. Akrotiri was naïve enough to announce on

the R/T that the Battle Flight was “scrambling” - all very 1940 and

gung ho!

Eventually someone came up with the bright idea of a completely silent scramble. The pilot took off without any calls, accelerating to Mach 1.3 at 25,000 feet. Then guided by ground radar, once in position the pilot turned his own radar on and completed the intercept. The target was visibly surprised the first time. |

It has been said in those days that you would meet the entire RAF if you stood in the Akrotiri mess bar for long enough

since they were visited by countless detachments from the UK as well as aircraft

en-route to the Far East.

56 squadron had a slightly unfair reputation for not being very hospitable, but

they were only 15 pilots set against hundreds of visiting aircraft. The record for a

"kebab" hosted by 56 in Limassol was 139 people.

To maintain air to

air refueling practice, Akrotiri was visited by a Victor K1 tanker every few months.

As a result someone decided that they could use the tanker to enable

them to intercept visitors rather further away than the usual 30nm or so. One

day Akrotiri was due to be visited by the very first Phantom detachment (from 54 Sqn).

It had been 56s habit to intercept all fast-jet visitors. After much bar planning, it was decided to mount one of the first ever tanker CAPs at about 60nm west of Akrotiri. OCA and

Andy were the first pair and duly sat with the tanker awaiting GCI information. They were duly

informed of a target and as planned set up in long line astern.

OCA, the leader was some 10-15 nm ahead of Andy going well when OCA saw the target visually and announced, in somewhat miffed tones, that it was a Vulcan and he was going back to the tanker.

At this stage

radar announced that they had a real target; 27 miles on the nose!

Andy....

|

None of this "joining on the port and waving at the captain" stuff! |

"With the defence of the Near East resting on my youthful shoulders this was no time for caution. The Phantoms were doing about 480kts and, as I failed to notice, were descending from cruise altitude to low level. I pressed on regardless and eventually claimed my kill at about 3,000ft. What I signally failed to check was my fuel state and the distance from base. Normally this would have been no real problem as most intercepts were very close in, but this was 110nm away. There seemed to be a great deal more sea between me and the runway than there was fuel in my tanks. Fortunately there were more professional aviators around than I that day and the tanker captain, Jock Carrol (OC Standards at Marham I believe) was doing his Mach 0.72 best to keep up. The threat of a few MAYDAY calls got a good heading to the tanker and while Jock swapped OCA from the good hose to the dodgy one, l completed the smoothest tanker join and contact in history; none of this "joining on the port and waving at the captain" stuff! Actually, l think he backed it on. I didn't go below 20001b fuel for weeks after that." |

Andy reports that he was lucky to serve on a squadron under 2 flight commanders with considerable vision. The first was largely responsible for the different and very realistic way of training that 56 adopted. The second helped

him enormously and allowed a callow youth to avoid too many mistakes. Although

56 suffered from terrible serviceability and poor aircraft availability – to the extent that 11 Squadron had to be deployed to help

cover the Battle Flight commitment – the flying was excellent. 56 also enjoyed a first-class relationship with 280 Signals Unit,

their resident control and reporting radar unit. Some of the Squadron’s tactics led the way to improvements in the way the UK squadrons operated.

The squadron was lucky to have so many visitors so they could practise against a variety of threats from resident Canberras and later Vulcans, through visiting Buccaneers, Phantoms and Harriers.

Andy remains eternally grateful that he drew this wonderful tour out of a hat – not to mention

Andy's wife who served at 280 SU.

(This

is an expurgated version of Andy Griffin's story - Click here for the complete

version)

|

1968 - Tragedy in Singapore - Pete Thompson

On 12 September 1968 Pete Thompson (89C) was piloting the second aircraft of a pair of 74 Squadron Lightnings recovering to Tengah. Whilst downwind, a reheat fire warning was illuminated but Peter elected to attempt to land. Without warning his aircraft pitched up, dropped one wing and entered a flat spin. He ejected very close to the ground but the main parachute failed to deploy and he was killed on impact.

Subsequent investigations found that a wrongly-connected fuel line had allowed fuel to leak into the reheat bay and collect there, where it ignited. The resultant fire burnt through the magnesium alloy control rods, causing the nose to pitch up as elevator control was lost leaving Peter with no control.

|

|

1969 - Dodgy landing in Darwin - Dick Shuster

On 2nd August 1969 Dick Shuster (89C) was the pilot of a Canberra aircraft of No 81 Squadron, engaged on a routine training flight from Darwin Australia. He started a descent from 29,000 feet approximately 400 miles south of Darwin and almost immediately there was a loud bang and the cockpit filled with smoke. Dick found that he had no elevator control and correctly diagnosed that the explosive unit, which normally severs the elevator control rod during an ejection sequence, had operated.

Dick brought the aircraft under control using his tailplane incidence trim switch. He then flew the aircraft towards Darwin, which was the nearest suitable airfield. During the descent into Darwin Dick checked aircraft handling at low speed with the undercarriage down. He discovered that there was slow response to the trim control, but by judicious use of engine power and trim he could hold reasonably accurate speeds. Adjustments to the rate of descent could be achieved by airbrake selections, but he decided against the use of flaps since he had insufficient control to overcome the marked change of trim in the Canberra aircraft when the flaps are lowered. A flapless landing was therefore inevitable.

The weather at Darwin was good but the wind was gusting to 20 knots on the runway in use, which was not equipped with a barrier. Before starting a long gradual descent into Darwin Dick ordered the escape hatch to be jettisoned into the sea so that the navigator could eject quickly if control of the aircraft were lost. The speed and the correct rate of descent were maintained by holding the power constant, making slight trim adjustments, and by constantly cycling the airbrakes. The last part of the descent had to be made at higher speed than normal because of the crudeness of control; thus the final problem was the possibility of the aircraft ballooning uncontrollably into the air after touchdown. Dick was fully aware of this and as he trimmed to level out over the runway he throttled back, selected full air brake and opened his flare doors to destroy as much lift as possible, at the same time being ready to order his navigator to eject. As the result of his skill, forethought and perfect judgment the landing was made with no damage to the aircraft.

| For

his actions Dick received the Air Force Cross and was the first member of 89

entry to do so. The AFC citation states - "The incident reflects credit on both crew members but particularly on the

pilot and captain, Flight Lieutenant Shuster.

He is relatively inexperienced, yet he made a very cool assessment of his

problem and took firm control of his disabled aircraft which was particularly

difficult to fly. He would have been completely justified in abandoning an aircraft in such a

dangerous state 400 miles from a suitable airfield...... Had the aircraft crashed or been abandoned it is doubtful whether the

fault could ever have been positively identified.

This young pilot, at considerable personal risk saved an expensive

aircraft and made a valuable contribution to flight safety.

He displayed gallantry, determination and coolness of the highest order

in the face of danger. He demonstrated high ability, and a marked sense of

responsibility in an extreme situation which reflects the greatest credit upon

himself and is in keeping with the highest traditions of the Royal Air Force. |

|

1970 - Trained to take orders? - Officer's mess Tengah

|

Dick Northcote (89D) relates this brief tale about meeting up with Frank Whitehouse (89B) in Tengah around June 1970, just a few weeks before Frank's demise in 1970. Frank was on Lightnings on No 74 Tiger Sqn based in Tengah and I was visiting with no 54(F) Sqn flying Phantoms as part of a 5 week detachment on Ex Bersatu Padu. |

|

This exercise involved flying detachments from Singapore, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. The obvious place for the first aircrew meeting was the downstairs scruff's bar in the Officers Mess at Tengah. Some 100 aircrew crowded into the bar and got stuck in. This was around 5pm. The bar itself was tailor-made for the occasion being about 50 yards long and manned by around 5 barmen.

Around 6pm I spotted Frank at the far end of the bar just as he spotted me. We had not met since 1966. We started to make our way towards each other through the by now rather merry crowd. Unfortunately one of the chaps decided to throw a rugby ball into the middle of the crowd and a huge scrum ensued. After a bit of a struggle and a few bad tackles, we finally shook hands, extracted ourselves and found a place at the bar to carry on with the beers. It was at this point that the PMC appeared in the doorway and called for quiet. I should point out that virtually the whole crowd were in shorts as was allowed.... up to a point.

" Gentlemen you should be aware that mess rules do not allow shorts in the bar after

6pm". There was a short pause (no pun intended) and without a by-your-leave, the whole crowd removed their shorts and called for more beer.

Frank and I continued the detachment in a similar vein and I was probably the last person to fly with him when he took me up for a trip in the 2 seater Lightning.

As we all know, a few weeks later when we had all returned to our home bases, sadly Frank died demonstrating a vertical climb after takeoff from Tengah. A great guy of whom I'm sure we all have fond memories.

[Les Quigley - We do -"Ill never forget the College Hall Porter's eyes when Frank, stark naked, wet and still dripping, led 2 of us (me fully dressed but completely soaked) through the main entrance of the College and across the "sacred carpet" at around 01:00 Hrs (The "Meakon" - {the Hall Porter's nick name} - really did look his name!). Our conditions reflected the fact that we had both lost in the game of Pirates on the lake of a local country club. "Pirates" involved as many cadets as possible cramming into row boats and kayaks all wielding drill swords with opposing squadrons attacking each other. Frank fell out of his row boat whilst my kayak rolled over and turned into a submarine. This left us both rather wet. Frank was driving us back to College so he whipped off all his clothes to save wetting his car - I kept mine on as there were ladies about!]

1970 - Another 74 Squadron Tragedy in Singapore - Frank Whitehouse

| On 27 July 1970 Frank Whitehouse (89B) was piloting Lightning XS930 and was the second aircraft of a pair. The pilots were briefed to carry out a rotation take-off. This required them to climb very steeply. XS930 stalled at approximately 600 feet and fell out of the sky. Frank ejected but was too close to the ground, his parachute failed to open so he was killed on impact. The aircraft hit a built up area killing two civilians and destroying & damaging over one hundred private buildings. Because the rotation take-off was not a common event it and the total tragedy was being filmed. |

|

After a full funeral service and cremation in Singapore, Frank's ashes were flown home and interred in the Commonwealth War Graves section at Cranwell village church cemetery.

The subsequent investigation determined that following an accident to another Lightning (XS928) earlier in the same year, a new approach to fuel management had been adopted, following advice from BAC, the Lightning’s manufacturer. The change meant that the flight refuel fuel switch was selected until the aircraft was airborne. This meant that the ventral tank fuel pump was not selected and therefore not working whilst the aircraft was on the ground. The reason for this was that XS928 had suffered fire damage due to fuel venting onto its wings whilst on the ground at Tengah.

The investigation determined that this new approach was flawed as it was not realised that using the fuel from the wing tanks instead of the ventral tank would move the centre of gravity

towards the tail. On the mission that saw the loss of Frank in XS930, the aircraft had to wait on the ground and taxi further to reach the runway, meaning a higher consumption of the fuel in the wing tanks. It was established by the Board of Inquiry that the CoG was moved outside of safe limits. This meant that when the pilot pulled hard on the control column to initiate a steep take-off, the aircraft over-rotated, climbing nearly vertically and reaching approximately 500 feet purely due to the reheated thrust of the engines before stalling.

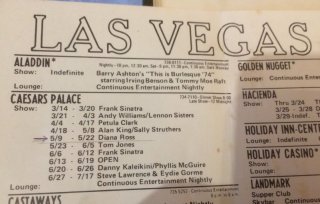

1974 - Pilots from 89 A, B & D Squadrons meet up in Las Vegas

In 1974, some 8 years after graduating, Black Robertson, Dick Northcote and Ron Shimmons found themselves on exchange tours in the States

Black was at Luke AFB, Arizona as an Instructor Pilot on Phantoms, Dick was there too doing the

Instructor Pilot course prior to his tour at MacDill AFB in Florida and Ron was flying U2s from Edwards AFB,

California.

|

Black Robertson |

Ron Shimmons (Right) with (left) Ian McBride, another RAF exchange officer |

Dick Northcote |

| It seemed churlish not to meet at a central point for a weekend together and Las Vegas was only a short 5-hour drive away for everyone.

So it was that in May 1974 the 3 of them, with wives, found themselves at a table for 6 in Caesars Palace watching a magnificent performance by Diana Ross. Not exactly something they expected to be doing when they last met together at Cranwell. The weekend was a great success, the casinos helped themselves to their dollars and they all then went their separate ways to continue their tours. |

|

1982 - Falklands War Veterans

1982 - Leading 1 Squadron - Pete Squire

|

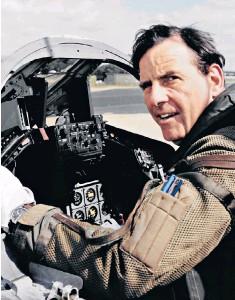

Pete Squire |

In 1982

Peter Squire (89A) commanded 1 squadron in the Falklands War. Jerry Pook

also of 89A was one of his Flight Commanders.

They flew with the squadron to CFB Goose Bay in Canada on 13 April 1982, on a six-hour flight using air-to-air refuelling for an exercise. The squadron departed for the Falklands on 3 May 1982 from RAF St Mawgan, flying to RAF Ascension Island, where a few days later it boarded the merchant transport ship SS Atlantic Conveyor. Arriving in the South Atlantic Ocean, the squadron transferred from the Atlantic Conveyor to HMS Hermes, a few days before the Atlantic Conveyor was attacked by the Argentine Navy sunk by two Exocet missiles. No.1 (F) Squadron was the first R.A.F. unit to operate in a combat role from a British aircraft carrier since the World War II. With No.1 (F) Squadron R.A.F. assigned to a ground-attack role in the conflict, Peter personally flew twenty four sorties against Argentine positions in support of British Army and Royal Marines operations on West Falkland and East Falkland. During one attack a 7.62mm bullet fired from the ground penetrated his harrier's cockpit. |

| On 8 June 1982

Peter suffered an engine failure whilst landing at a forward operating base behind British lines at San Carlos and crashed the

aircraft, walking away uninjured. On 13 June 1982 he was the first R.A.F. pilot to drop a laser-guided bomb in action during fighting at Mount

Longdon, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross

Four Harriers from No.1 (F) Squadron of its ten combat strength were lost during the war, three to enemy ground fire, and one (piloted by Peter) through engine failure whilst in flight. After the war, whilst still in the Falklands, on 6 November 1982 Peter again suffered engine failure whilst out on a routine patrol, and was forced to eject from the aircraft at low altitude near Cape Pembroke, being rescued from the sea uninjured by a Royal Navy helicopter |

|

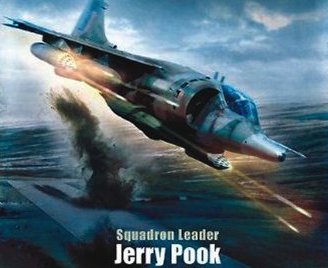

1982 - Jerry Pook earns his DFC

|

|

Jerry Pook (89A) was flight commander in 1(F) Squadron. He had been nominated mission leader throughout the invasion phase, conducting 23 attack sorties from the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes. Jerry led missions on 21 and 27 May 1982 which destroyed probably four Argentinian helicopters, with him personally destroying two Pumas on the ground despite SA and SAM defences. He also led two successful attacks on Goose Green in the face of very heavy anti-aircraft fire, the second against a large calibre gun which was destroyed causing heavy casualties; this helped 2 Para Regt obtain the surrender of the troops in that area. On 30 May 1982 Jerry's Harrier was hit while attacking a gun position on Mount Harriet. He nevertheless pressed home his attack but, as a result of system damage to his aircraft, he had to eject over the sea 30 NM from HMS HERMES. As he descended in his parachute he recalls the relief of hearing the navy's helicopters coming to his aid. This relief was soon tempered when he hit the ice cold South Atlantic water and had difficulty with his life raft. Luckily the Navy arrived in the nick of time to pluck him out of the water. |

Despite his ordeal Jerry was back on operations within 48 hours. His DFC citation states ...

"His determination was undiminished by the experience and he has continued to display considerable courage and great professionalism."